The following article is published with the kind permission of the author Simon Goodwin, Hertfordshire Constabulary Great War Society and Dr. F.R.J. Newman PhD - editor of Trench Foot Notes.

On recent visits to the Ypres Salient and the Somme it struck me that I had been visiting military cemeteries for many years but had I really been seeing and understanding all that was involved in their architecture and construction. A little research unveiled the following, very basic, facts ….

French Cemeteries

A French law was passed on the 29th December 1915 calling for the creation of national cemeteries to bring together the bodies of those soldiers who “died for France”. These were to include perpetual graves maintained at the expense of the state. In July 1920 a further law was passed which, for the first time, allowed for families to request the return of the bodies of their loved ones for burial in their own family vaults. Approximately, 30% of those bodies identified, some 250,000 men, were moved in this way out of national cemeteries. In total, France now has 265 cemeteries which hold 730,000 identified and unidentified bodies.

The design of French cemeteries was very much concerned with practical rather than architectural imperatives, France was suffering heavy finance burdens after the war with the costs of rebuilding French towns and villages and supporting the widows and orphans of soldiers. Indeed, the cemetery plans were drawn up by technicians from the Pensions Ministry, rather than Architects.

A standard layout was adopted in 1928 with a central flagpole and the graves laid out in rows in reflection of army lines. The only touch of bright colour would be provided by red rose bushes.

There are four types of emblems to be found in French Military Cemeteries – Latin crosses, Muslim headstones (about 160,000 colonial troops fought in the French army of whom 30,000 died), Jewish headstones and headstones for other religions or freethinkers (France is the only nation to have created a special headstone for agnostics or free thinkers). In the design of its cemeteries the French Republic reasserted the principle of the secular state, freedom of belief and freedom of thought.

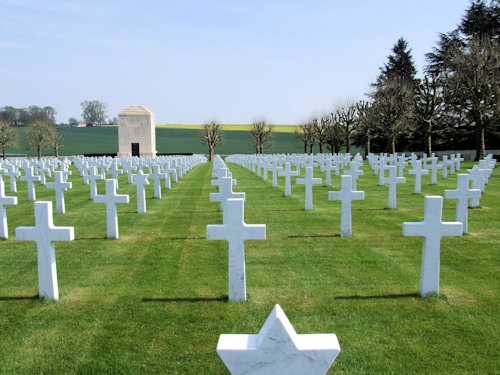

American Cemeteries

During the First World War the US War Department built eight military cemeteries and fourteen monuments on the battlefields to honour the US dead.

The American Battle Monuments Commission was established by Act Of Congress in March 1923. Its goal was to construct and maintain memorials in the United States and overseas where US armed forces had served since 6th April 1917 (the day the United States declared war on Germany).

In 1934 the ABMC took over the management of all the overseas cemeteries and monuments from the War Office and they ensured that a chapel was built in each of the eight cemeteries.

German Cemeteries

It wasn’t until 1926 that the Volksbund Deutsche Kriegsgraberfursorge (VDK), the German War Graves Commission, was finally allowed to intervene in German Military Cemeteries in France. Prior to that time the French authorities had already moved numerous German bodies to form large concentration cemeteries - but these were simple unfenced fields with wooden crosses.

The Treaty Of Versailles had provided that German Cemeteries were to be under the guardianship of the French Authorities. During this time, the French had the final say of any developments of permanent building work undertaken in the cemeteries and they also refused to return the German bodies to their families.

The German cemeteries we see today were designed and constructed during the inter war years by architect Robert Tischler, a Great War veteran. Due to the cramped nature of the areas allocated by the French, burials were carried out in large communal graves, called “Comrades Graves”. The design was a deliberate one - to blend in with their environment, plants are allowed to grow freely and trees are not pollarded - this fits in with German mythologies concept of communion between man and nature.

In the 1920s the VDK used wooden crosses with a zinc plate, or stone slabs laid on the ground, to mark individual graves but by the 1950s a decision was taken to generalise the use of erect crosses to give a better visual portrayal of the extent of the slaughter and for these to be made from durable materials such as aluminium, cast iron or stone.

Only in 1966, with the advent of the European Union and initiatives for Franco-German reconciliation, was the upkeep of the cemeteries surrendered by the French and passed to the VDK.

British Cemeteries

During the first few weeks of the Great War the bodies of the dead were, wherever possible, repatriated but it soon became clear that this could not continue so bodies were soon buried where they fell. Post the war there were some attempts to “consolidate” some cemeteries but many small burial areas still remain. The Imperial War Graves Commission, the precursor of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, also insisted that the dead not be brought home after the war because that contravened the idea that all casualties were equal in death and some families, having the funds to bring a body home, should not create a different treatment. This idea also extended to the gravestones which were all to be the same size and shape to prevent the risk of more ornate graves being used for the more wealthy.

It was the Catholic Church who argued for the addition of certain individual lines of text at the base of headstones as they contested that, amid the slaughter, there was rarely time to say the last rites to each dying man and they demanded space for a prayer to speed the soul through purgatory. Of course, if it was good enough for the Catholics then why not everyone else.

There were also attempts made to accommodate the traditions of certain ethnic groups fighting in the army, for example, the Neuve Chappelle Memorial bears the names of the Indian soldiers whose bodies were cremated. Many British soldiers are also to be found buried in special plots within French municipal cemeteries.

Three British architects supervised and directed the development of the Commonwealth cemeteries in the period just after the First World War, Reginald Blomfield, Herbert Baker and Edwin Lutyens. The cemeteries were to be gardens, a reconstitution of the paradise lost where Man once lived in peace and harmony with nature. Trees, bushes and flowers were included to add colour and scent throughout the seasons. Sir Reginald Blomfield, who designed the first three cemeteries, was enthusiastic about horticulture having previously designed parks and gardens – so the die was cast.

Graves can sometimes appear to be arranged in what seems a random order and facing different directions. This often reflects the original position of the graves. Sometimes gravestones touch each other, most often in the cases of soldiers killed in the same trench (e.g. the Owl Trench Cemetery at Hebuterne).

It was decided that for all burials a simple headstone would be used and the families were asked is they wanted a Christian cross, a Star of David or a Muslim symbol on the grave. In addition, as identified above, the Commission gave families the opportunity to have an epitaph engraved on the bottom of the stones. This was to be to a maximum length of 66 characters, including spaces, (to fit to the confines of the stone) and subject to a charge of 3 ½ pence per letter – many thought this was “penny pinching” by the Commission. 3 ½ pence per letter x 66 worked out to be the equivalent of just under one old Pound, this equalled the pay of a skilled tradesman for three days work and could be approximated to £400 in today’s money. Clearly, shorter inscriptions would have cost significantly less. The Commission also stipulated that no special alphabets, such as Greek, could be accepted. The New Zealand government, enraged by the charges and the limited message length, went so far as to decide there could be no fitting epitaph for their soldiers that would express the feelings of grief, so none were submitted for any New Zealand headstones. The Canadian and Australian governments took a different tack and insisted that they would pay for all the inscriptions for their soldiers, and not ask for any money from the families. Even for those who requested an epitaph, it appears that some families paid up and others didn’t and in the end it became almost a voluntary thing. Of course, sadly, had more families known that payment would have ended up being voluntary they might have asked for inscriptions as well. The epitaph request forms, to be completed by the next of kin, also asked the age of the casualty. For that reason a headstone showing the age of the casualty almost always bears an epitaph and vice versa.

In principle the Commission had the right to censor the messages – a power used to exclude one example when a request was received for “His dad and mum hate the Hun” which, upon rejection by the Commission, was changed by the family to “With every breath we draw, we hate the Hun more” which was also, unsurprisingly, rejected.

There was unhappiness from many families about not being able to erect a personal memorial to their loved ones.

Sir Edwin Lutyens and his team designed 126 cemeteries in France and Belgium, he insisted they be a part of the landscape, visible from the outside and contain a combination of stone features and vegetation. The garden designer Gertrude Jekyll also became involved and she inspired the choice of planted borders in front of the graves. Simple cottage garden plants were chosen and soft, closely mown, plain grass was incorporated as it eliminated differences and encouraged peace. It was Lutyens who designed the War Stone or Stone Of Remembrance to be erected in cemeteries with over 400 graves. The War Stone was designed using the classical principle of entasis – the Greek rule of optical correction used at the Parthenon, to mathematically correct the structure to make it more pleasing to the eye. Each stone is 3.5 metres in length and 1.5 metres high and it sits on three shallow steps. Entasis was applied to all the horizontal and vertical edges of the stone - there are no straight lines anywhere on the structure. Should these curves be extended they would form a series of imaginary circles over 1,800 feet in diameter.

Sir Reginald Blomfield went on to design the “Cross of Sacrifice” to be erected in cemeteries containing more than 40 graves. The finished crosses ranged from 4.5 to 9 metres in height and featured an inverted bronze sword, a sign of mourning. The crosses are also tapered using the optical correction technique of entasis and both the shaft and the cross arms are octagonal. The base was also octagonal and allowed further flexibility meaning that the whole structure could be incorporated in to walls or positioned to allow seating features at its base.

The CWGC now maintains about 470,000 headstones in 153 countries and commemorates the memory of 1.7 million men and women. A specially commissioned audit in 2014 estimated that there were about 70,000 headstones that currently needed replacing due to weathering and other damage. On the back of this, production at the CWGC workshop in France was upped from 6,000 to 22,000 headstones a year.

The headstones are specially engraved at a 60 degrees angle rather than the standard 45 degrees. As a visitor looks at a headstone, generally speaking from a respectful distance of 6 feet, they are seeing the stones at an angle of 45 degrees and there would be no shadow – engraving at 60 degrees mean that there is a shadow and this makes the wording easier to read in each character. There are 34 different types of headstone and up to four different types of stones per marker shape.

Simon Goodwin 11th July 2018

Bibliography

The National Characteristics Of Cemeteries – Remembrance Trails Of The Great War in Northern France Yves Le Maner

“If this is victory, then let God stop all wars” : the revealing 66-letter epitaphs on the graves of the Somme dead” Robert Colville

“Work On Headstones Is An Honour” London Evening Standard

“Architecture” CWGC Website

“The American Battle Monuments Commission” The Great War 1914-18