The following article is published with the kind permission of the author George Wilson, Hertfordshire Constabulary Great War Society and Dr. F.R.J. Newman PhD - editor of Trench Foot Notes.

THE SCUTTLING OF THE GERMAN HIGH SEAS FLEET

AT SCAPA FLOW ON 21ST JUNE 1919

George Wilson

Although this article is principally concerned with the scuttling of the German ships at Scapa Flow on 21st June 1919, it is important to know why and how the German Fleet were at the British base eight months after the Armistice was signed on 11th November 1918.

In the decade before the First World War Germany embarked on a large naval shipbuilding effort, but was unable to match the British superiority in capital ships. As one prescient British naval historian said, “It [the Germany Navy] was not strong enough in time of war to protect German commerce or the German colonies, or to meet its main rival in battle on the open sea”[1]

The German Navy did venture out to seek battle with its British opponents, the shelling of British coastal towns, for example Scarborough and Hartlepool, the battle of the Dogger Bank and the much larger engagement at Jutland beginning on 31st May 1916, the latter involving a high proportion of the German High Seas Fleet. Despite the British suffering more serious losses of capital ships and manpower than its enemy, Jutland convinced German naval leaders they could not sustain their own losses; as a result the German High Seas Fleet returned to the safety of German ports never again to venture out in great strength to challenge Great Britain’s grip on the North Sea. Nor could they break the British naval blockade of Germany.

Their riposte was to unleash their submarines to attack both naval and mercantile civilian shipping, becoming infamous as unrestricted submarine warfare. This caused serious problems for the British with food and war material shortages starting to hinder the prosecution of the war. However once convoy systems were introduced by the British naval planners, the situation eased considerably. In essence Germany could no longer hope to win the war by this method.

The success of the British, French armies and the entry of the United States of America on the battlefields of the Western Front resulted in Germany seeking an Armistice. The German Navy contributed to the realisation that Germany had lost the war after Admiral Hipper’s plan which envisaged a last sortie by the High Seas Fleet on 29th October 1918 “…viewed by most of his ship’s companies as a ‘death ride’, was scuppered by the crews refusing to sail”[2] This was soon followed by a mutiny by the crews of most capital ships. By 9th November the navy could no longer be relied upon, and on the same day the Kaiser abdicated.

When the Armistice was signed on 11th November 1918, one condition of the agreement demanded the entire German U-Boat fleet be surrendered and confiscated immediately. The Allies as this juncture had not yet decided what to do with the surface ships of the German High Seas Fleet. A decision was made they should be interned in Allied or neutral ports until their fate could be agreed during peace negotiations. Spain and Norway were suggested as neutral ports, but both countries declined.

Admiral Wemyss, the senior British naval officer present at the Armistice negotiations suggested that the German fleet be interned at Scapa Flow with a skeleton crew of German sailors and guarded in the interim by the British Grand Fleet.

Admiral Beatty the Commander-in-Chief of the Royal Navy’s Grand Fleet, set out the terms of the surrender to German Rear Admiral Hugo Meurer and other officers aboard his flagship, the battleship HMS Queen Elizabeth on the night of 15/16th November 1918. The terms were expanded at a second meeting the following day. The U-Boats were to surrender to Rear-Admiral Tyrwhitt at Harwich, under the supervision of the Harwich Force. The surface fleet was to sail to the Firth of Forth and surrender to Beatty. They would then be led to Scapa Flow and interned, pending the outcome of the peace negotiations. Meurer asked for an extension to the deadline, aware that the sailors were still in a mutinous mood and his officers might have difficulty in getting them to obey orders; he eventually signed the terms after midnight. Included in the terms was the surrender of 74 vessels (excluding U-Boats). The procedure was named Operation ZZ.

The first German submarines began to arrive at Harwich on 20th November, 176 were eventually handed over. Admiral Franz von Hipper the commander of the German Navy, refused personally to surrender the German High Seas Fleet to Admiral Beatty; he delegated this task to Rear Admiral Ludwig von Reuter. On 19th November the fleet of German warships led by von Reuter in his flagship the battleship Friedrich der Grosse left Germany to rendezvous with Beatty’s ships in the North Sea.

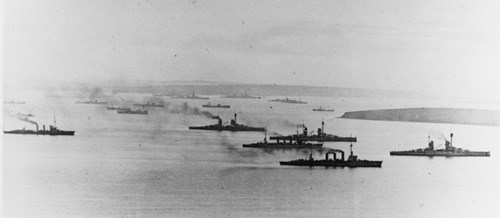

They arrived on the morning of 21st November and were met by an Allied force of about 250 ships, which included most of the Grand Fleet, an American Battleship Squadron and representatives of other navies totalling 44 capital ships. The German fleet was escorted into their allocated anchorage in the Firth of Forth. Once all the German fleet had dropped anchor, Beatty gave the signal that the German flag was to be hauled down and not to be raised again without permission – a controversial move given the ships remained the property of Germany during internment.

Once disarmament checks had been completed, the German ships sailed under heavy Allied escort between 25th and 27th November for internment at the massive natural harbour at Scapa Flow in the Orkney Islands. The final ship to arrive was the flagship of the High Seas Fleet, the dreadnought battleship Baden in January 1919, thus fulfilling the requirement that 74 ships be interned under the terms of the agreement. The interned vessels consisted of 11 battleships, 5 battle cruisers, 8 light cruisers and 50 destroyers.

Scapa Flow is a body of water about 120 square miles in area with an average depth of 30 to 40 metres. The Orkney mainland and South Isles encircle Scapa Flow, making it a sheltered harbour with easy access to both the North Sea and Atlantic Ocean. The name Scapa Flow comes from the Old Norse Skalpaflol, meaning ‘bay of the long isthmus’, which refers to the thin strip of land between Scapa Bay and the town of Kirkwall.

Initially the interned vessels were guarded by a Battle Cruiser Force, later reduced to a Battle Cruiser Squadron. From the 18th May 1920 the responsibility for guarding the German ships was the responsibility of Vice Admiral Sir Sydney Freemantle commanding the First Battle Squadron.

Whether by accident or design the internment location was very isolated. Initially there were about 20,000 German sailors on the ships, but gradually these numbers were reduced at regular intervals by sending them back to Germany (when the scuttling took place the numbers still at Scapa Flow was about 1,700). During internment the sailors were not classed as prisoners of war, consequently there were no British naval personnel assigned to guard duties on the 74 German ships. No British personnel were allowed to visit the German ships except on official business.

The responsibility for feeding the internees rested with the German government; none of them were allowed to leave their ships and were not permitted to speak to any of the local inhabitants. A British naval historian Arthur Marder described the state of affairs on board the German ships as “one of complete demoralization”, he identified four reasons that exacerbated the situation: lack of discipline, poor food, lack of recreation and slow postal service. The cumulative result was “indescribable filth in some of the ships”. With no fresh meat supplies and being forbidden to change ships, the sailors sought their own recreation and food supplies. Fishing was an ideal way to pass the time and supplement their diets. On one destroyer the crew built a spring-loaded gun to kill seagulls to eat.

As the peace negotiations dragged on with no end in sight, Rear Admiral Reuter was faced with troublesome groups of sailors aboard his own flagship, a situation which became so unmanageable that he fought permission from the British (granted) to make the flagship the Cruisier Emden his new flagship. As the Paris Peace Conference discussions continued and were delayed until the end of June 1919, the Allies remained divided over the fate of the ships. Most wanted a share for their navies, but Britain wanted the ships to be scrapped to prevent other nations from gaining naval superiority.

By May the fate of the German fleet was still to be decided, but the Armistice agreement was due to expire on 21st June 1919 when the Peace Treaty would become effective. With the passage of time von Reuter became fearful that the British would seize control of all the interned ships at Scapa Flow without notice if the Treaty arrangements were not in place. According to some historians, Reuter had been considering taking the drastic decision to scuttle the fleet.

The British Navy hierarchy too were well aware that as the Treaty deadline approached there was a danger of scuttling. Under Article XXXI of the Armistice, the Germans were not permitted to destroy their ships but Admiral Beatty and his senior officers had provisional plans if necessary to seize the ships. Admiral Freemantle submitted a plan on 16th June for seizing the German ships at midnight on the night of 21st/22nd June, after the Treaty had been signed. This was approved on 19th June, but only after the deadline for the signing of the Treaty had been extended to 1900 hours on 23rd June. Freemantle was not officially informed of the extension – he read about the extension in a newspaper on the same day and assumed it to be true.

In fact the parties to the proposed Treaty of Versailles met on 22nd June. With just four hours to meet the deadline the German delegates agreed to sign all the clauses except those relating to ‘war guilt’. The Germans asked for a forty eight hour delay to consider their position. By this time the Allied representatives had learnt of the scuttling of the German fleet. As a result they were given twenty four hours to sign the Treaty or face the consequences. Before the expiry of the ultimatum they agreed. (The formal signing of the Treaty took place on 28th June).

For some time Freemantle had been tasked to conduct an exercise with his battleships against torpedo attacks, which required good weather to recover the torpedoes. The weather on the night of 21st June was favourable so he ordered the First Battle Squadron to sea at 0900 the next morning – 21st June. As a result the operation to seize the German ships was postponed until the night of his squadron’s return to Scapa Flow on 23rd June (after the deadline to sign had expired)

The departure of the First Battle Squadron left only a very small British naval presence at Scapa Flow, consisting of two destroyers Vespa and Vega, plus a couple of depot ships and various trawlers and drifters. Von Reuter seized his opportunity. On or about the 18th June the crews of the interned vessels had been making surreptitious preparations for scuttling. Admiral von Reuter had informed the officers on his ships of his intention by smuggling from ship to ship written orders carried aboard one of the British mail drafters – a normal method of communicating with his ships crews.

The prearranged signal to scuttle was given by von Reuter at about 10.30am on 21st June. The message said: ‘Paragraph eleven. Confirm’. It took about an hour for the message to reach all the German ships. It was confirmed by semaphore and searchlights. The crews opened seacocks, torpedo tubes and portholes to flood them and the flags of the Imperial German Navy were hoisted.

The first inclination of the scuttling came when various ships started to list, prompting an urgent signal from the British navy at Scapa Flow to Rear Admiral Freemantle, exercising his squadron. He returned at full speed, arriving back about 2.30pm where he found only the large ships still afloat. Whilst sailing at full speed he radioed ahead for all available craft to prevent German ships sinking or to beach them.

The last German vessel to sink was the battlecruiser Hindenburg at 5pm. By this time 15 out of the 16 capital ships had sunk. The British managed to beach the Beaden and the cruisers Nornberg, Emden and Frankfurt. Four light cruisers and 32 destroyers were also sunk. The crews of the German ships took to lifeboats when during the chaos, 9 German sailors were killed and 16 wounded.

Von Reuter and his men were informed they had broken the terms of the Armistice; as a result they were to be regarded as prisoners of war and subsequently transported to a POW camp at Nigg where they remained until released including von Reuter, and returned to Germany after the provisions of the various treaties were complied with.

The 52 scuttled ships amounted to about 400,000 tons lay in Scapa Flow; some of the beached ships were handed over to Allied navies. Britain joined in the condemnation of the German action, including Admiral Wemyss, who had suggested the internment in in the first place, who in private considered it a relief arguing ‘It disposes, once and for all, the thorny question of the distribution of the ships’.

Initially there was no great desire to raise the sunken ships, the cost of salvaging them not being worthy of the potential returns due to the glut of scrap metal after the end of the war, with plenty of obsolete warships being broken up. However the wrecks prevented the use of piers and fishing stations, and were a hazard to shipping. This, plus pressure from the local community resulted in the Admiralty sanctioning the sale of most of the sunken ships.

From the early 1920s, various private companies, including Ernest Cox & Danks Ltd raised and salvaged most of the ships. Currently 7 vessels remain in the deeper parts of Scapa Flow. In 2001 they were given protected status under the Ancient Monuments and Archaeological Areas Act 1979 (ref: SM 9298 & SM 39308). The wrecks have a world-wide reputation for superb diving, but divers need a permit to do so.

The scuttling of most of the German High Seas Fleet was celebrated as a triumph by many Germans, particularly in the high echelons of the German navy, who preferred its self-destruction rather than being handed over piecemeal to the Allies. This sentiment is punctured by the last twelve words quoted by Julian Thompson (he commanded a Royal Marine Brigade during the Falklands War) in the penultimate chapter of his book when he describes the last journey of the German Fleet: ‘The next time the High Seas Fleet came out [from its base in Germany] was to surrender’ [3]

[1] Julian Thompson: The War at Sea 1914-1918 (London: Pan Books 2006), p.50

[2] Julian Thompson : The War at Sea, p.428

[3] Julian Thompson: The War at Sea, p. 428

SOURCES:

Books: (Thompson) The War at Sea 1914-1918, Dictionary of the First World War, (Gilbert) First World War

Websites: Imperial War Museum, History Navy, History Beneath the Waves, World War One, Salvage Operations in Scapa Flow, BBC (Scotland), Wikipedia