Name

Francis John (Jack) Pearce

Conflict

First World War

Date of Death / Age

09/09/1918

19

Rank, Service Number & Service Details

Rifleman

O/127

Rifle Brigade

Posted to 1st/8th Bn. London Regiment

Awards: Service Medals/Honour Awards

British War and Victory medals

Cemetery/Memorial: Name/Reference/Country

EPEHY WOOD FARM CEMETERY, EPEHY

V. I. 2.

France

Headstone Inscription

Not Researched

UK & Other Memorials

Pirton Village Memorial,

St Mary’s Shrine, Pirton,

Methodist Chapel Plaque, Pirton,

Pirton School Memorial

Biography

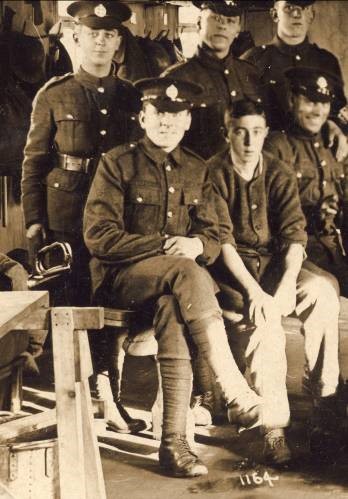

He was also known as Jack and appears as John in 1901 and 1911 census, but appears as Francis on the Village Memorial and, as that is how they wished him to be remembered, that is how he appears here.

Francis was the son of George and Ellen Pearce (nee Burton) and was the half-brother of Edward Charles Burton, who also served and died. The sibling relationships were complicated and they are described more fully in the chapter on Edward. However, in brief, George married Ellen some time around 1898 or 1899 and Ellen already had a son, Edward Charles Burton. So Francis was Ellen’s second son, but the first child from the marriage. He was born in Pirton on December 19th 1898 and they lived in one of the Holwell Cottages – the row of twelve terraced houses on the Holwell Road, also known as the ‘Twelve Apostles’. Francis went to the village school and in the 1911 census he was still recorded as a scholar and aged twelve.

After leaving school he went to work for Innes’ Sons and King, Hitchin, and was working there when he joined the army. According to the Parish Magazine, that was some time after March 2nd 1917 and then in June 1917 it recorded him as being in the Training Reserve Battalion, but gives no further details. His elder brother or half-brother Edward Charles Burton was killed in December 1916 and one wonders if that influenced Francis to enlist or whether he was conscripted – conscription began on January 27th 1916.

His Battalion is one of those known as the ‘Post Office Rifles’, the full Battalion name is almost certainly the 1/8th (City of London) Battalion (Post Office Rifles) and, as the name suggests, was one of the Battalions substantially made up of volunteers from amongst the Post Office workers. This was not unique to the First World War as there was a long tradition of Post Office workers joining and serving in the army at the time of war. 1914 saw this tradition continue and they went on to serve with distinction at Ypres, at Passchendaele and elsewhere. During September 1917 they lost more than half their strength in the Battle of Wurst Farm Ridge and so the number of Post Office workers in the battalions was diluted by new recruits such as Francis.

He went to France on January 10th 1918, but whether that is when he joined Post Office Rifles is not yet known. If it was, then he joined them after their part in the Battle of Passchendaele or the Third Battle of Ypres, where they suffered more heavy losses.

In the early part of January they were ordered to France, first to Villers-Bretonneux by train, then Moreuil and then, at the beginning of February, to Pierremande where they took over the southernmost part of the British line with the French to the south. They were there until March 19th when they had been moved out of the line to rest, but at 4:30am on the 21st the Germans launched a major offensive, this part of which was later called the Battle St. Quentin. At 5:00pm they were ordered forward and then at 10:30pm were ordered to protect the Crozat Canal crossing. The enemy were advancing and it did not look good; secret papers were removed from Battalion HQ and the British began blowing up bridges to stop the Germans. On the 22nd it was foggy, visibility was difficult and stragglers were still finding their way back from what had been the front line. At about midday Germans dressed in British uniforms, taken from dead or captured troops, came across on the Battalion’s left flank. That flank fell, largely because of these Germans, but “C” and “D” Companies held the right flank for 36 hours until the enemy were attacking them on three sides. It was recorded that very few escaped. The Germans began to pour forward; the British hit them with field artillery and massed machine gun fire. The fighting was desperate, but the hastily formed new defence lines held.

Between the 21st and the 25th the casualties in Francis’ Battalion were terrible: 13 officers, 4 killed, 8 more were missing. In the other ranks 300 were killed, wounded or missing. It is known that Francis had been wounded and by April 13th 1918, had been returned to England to Eastleigh Hospital in Hampshire. Francis himself made light of the injury writing to his family saying he was ‘slightly wounded’. It seems very likely that his injuries were received in the above battle.

He would have been out of the line for some time recovering and we do not know when he returned to the Battalion, but if it was by July 25th then he may have taken part in a large daylight raid - 300 men went over the top and attacked the German trenches. In the advance they met little resistance, except for one small section. They killed some Germans, captured a few prisoners and ‘many more in attempting escape had to be shot.’ However, on the return journey the Germans reorganised and opened up with machine guns on both flanks. Two Officers were killed, 4 wounded and the casualties in the other ranks were counted as 113. Their war diary notes ‘On the whole, it seems that the casualties on both sides were about equal.’ It was also noted, because it was unusual, that ‘the enemy allowed the wounded to be got in without interference.’

In early August they were withdrawn for a long period of rest and training in preparation for the next big offensive on the Somme. However, that was not to be and on the 6th they began the relief of the 2nd Bedfords near Sailly-Laurette. At dawn on the following day, still trying to complete the relief, they were attacked. Although the Germans pushed sections of the line back 400 yards they failed to break it. As the infantry attack petered out, the British front line continued to be pounded by large shells, gas shells and trench mortars. The British were planning their own offensive to begin on the 8th, which it did and began with success. The 1/8th London Battalion was held in reserve until the next day and so it was on the 9th that they went into the attack. They were joined by an American Regiment – from August 1918 the Americans were fully participating in the war. They record that the Battalion casualties were far lighter than the number of unwounded prisoners taken, but 4 officers were killed, 7 were wounded and 290 other ranks were listed as killed, wounded or missing. They were relieved two days later when they finally got some rest and yet more training. On August 22nd they moved back to the Front to support another attack, which took place during a violent thunderstorm. They had gone forward without water or rations and remained without either until the night of the 27th and then on the following day the attack was resumed.

Between the 22nd and the 28th they took 150 prisoners, captured three field guns, lots of machine guns and ‘forty enemy pigeons.’ Two officers were killed, 4 wounded and 186 other ranks were killed or wounded – they were given a day’s rest before the next attack. During this one, they lost 2 more officers, 5 more were wounded and 105 other ranks became casualties.

They were relieved on September 1st, but despite their horrendous losses were only allowed to remain out of the line until the 6th when they again moved forward for an attack on the 8th. Francis and his comrades must have wondered if it would ever end. They attacked on the 8th as planned, advancing an unbelievable 1,000 yards, but then came under heavy machine gun fire. The Royal Field Artillery, who had advanced behind them, poured shells onto the enemy. The Battalion was ordered to hold the gains at all costs; they did and Francis paid the ultimate price, being killed on the 9th. He was among another 141 other ranks killed or wounded.

Although Francis was killed in action on the September 9th, the family did not know. In November the Parish Magazine published what the family had been told, which was that he had been wounded and was missing. They must have prayed that he was a prisoner and being well treated, but those hopes were dashed when the news of his death finally came.

Perhaps his body was found quickly and the news just took time to reach Pirton, but it is possible that his body was found much later when land was retaken and was identified by his identity tags or other personal belongings. Perhaps some clues come from the history of Epehy, where he is buried. It is in the area known as the Somme and between Cambrai and Peronne. It was captured by the British in April 1917, but lost to the Germans in March 1918 only to be retaken in September 18th – nine days after Francis died. Clearly there was a lot of fighting, much confusion and many casualties as the control of areas of land moved between opposing forces.

Francis is buried in Epehy Wood Farm Cemetery, but he was first buried either on the battlefield, in Deelish Valley Cemetery, which originally contained 158 burials from September 1918, or in Epehy New British Cemetery, which also contained men who died in September 1918. The latter locations were close by and they were amalgamated into Epehy Wood Farm Cemetery after the Armistice.

The cemetery has an unusual entrance, constructed in stone and raised from the road. It is not the largest of cemeteries, containing only 997 burials, but once inside its appearance is striking and it is surrounded by views over miles of open, flat countryside. The Stone of Remembrance is placed at one end and at the other the Cross of Sacrifice is made even more poignant by the effect of two poplars rising like giant flames either side.

The losses of this Battalion are truly staggering; remembering that a Battalion is about 1,000 men in the 1/8th, Francis’ Battalion to January 31st 1918, the losses were killed 565, wounded 1,598 missing or killed 189, and from February 1st 1918, when they combined with the 2/8th forming the 8th, another 288 were killed 1,214, wounded, missing or killed 327. It seems that Francis was lucky to have survived so long.

Additional Information

Text from the book: The Pride of Pirton

Acknowledgments

The Pride of Pirton book – www.pirton.org.uk/prideofpirton Chris Ryan / Tony French / Jonty Wild