Name

George Thomas Trussell

Conflict

First World War

Date of Death / Age

10/04/1917

28

Rank, Service Number & Service Details

Private

G/22199

The Queen’s (Royal West Surrey Regiment)

6th Bn.

Awards: Service Medals/Honour Awards

British War and Victory medals

Cemetery/Memorial: Name/Reference/Country

ARRAS MEMORIAL

Bay 2.

France

Headstone Inscription

NA

UK & Other Memorials

Pirton Village War Memorial, St Mary’s Shrine, Pirton, Methodist Chapel Plaque, Pirton, Pirton School Memorial, St Mary's Church Roll of Honour (Book), Hitchin

Biography

The Commonwealth War Graves Commission records give Mrs. Elizabeth Trussell, of Burge End, Pirton, Hertfordshire, as George Trussell’s mother. She was formerly Elizabeth Pitts and recorded in the 1881 census as the daughter of James and Sarah Lowe, she was the second wife of James and the younger sister of his first wife, Ann Lowe. At that time she was unmarried, a spinster of the parish with two children: James (b c1875) and Alice (b 1880). On April 6th 1885 she married George Trussell and home was recorded as ‘near Burge End’ - a name given to a much larger area than the current road of that name. They had three children(*1) together, Ellen, Emily and George Thomas Trussell who was born in Pirton in October 1888. By then Elizabeth was a widow, as George (senior) died on April 19th 1888 and so George Trussell (junior) never knew his father.

The School Memorial confirms that he attended the school and by 1911 George he had left and was earning a living as a stable groom. A very brief Parish Magazine article, dated August 1916, confirms that he had joined up in 1916 and therefore he probably did not go to France until early1917.

The Battalion’s war diary records the period leading up to George’s death on April 10th 1917. March started off with the Battalion in the area around Lignereuil. On the 1st and 2nd they were in practice trenches near Givenchy-les-Noble where they rehearsed for an attack. They would not have known, but they were preparing for the Battle of Arras. On the 3rd and 4th they marched to Arras, billeting over night at Lattre St. Quentin. Between the 5th and the 15th they were in constant demand for working parties preparing the way for the launch of the major offensive. They were fortunate to only have three men were wounded during this period. On the 14th they did not finish their work until midnight and then marched for over six hours to reach billets in Montenescourt. One of the entries records the strength of the Battalion in France as 45 officers and 1,129 other ranks. After their efforts they remained in billets until the 19th.

On the 20th they marched for 3 ¼ hours to Lignereuill and they must have known that something big was in the air because the next four days were again spent practicing for a major attack. Heavy traffic on the roads meant a difficult march to Arras where they relieved the 9th Battalion, Essex Regiment who were in billets. Between the 26th and 29th they formed working parties and only suffered light losses and on the 30th moved into the front line, relieving the 6th Royal West Kent Regiment at 7:30am. They recorded a quiet night.

During the night of April 1st, the German artillery became more active and four other ranks were wounded. The next night they sent patrols to reconnoitre the German barbed wire and found that previous gaps they had made had not been repaired. It is possible that this was a deliberate strategy by the Germans as it would allow them to concentrate their machine gun fire on exactly the positions where the British would concentrate their troops. They were relieved on the 3rd and went to billets in the museum in Arras.

The British plan for the Battle of Arras moved into a new phase on April 4th and 2,800 British guns began a bombardment of the enemy lines on a fourteen mile front. The war diary notes the commencement of the bombardment and it seems that there was retaliation and there was a direct hit on the museum where the Battalion were billeted. That single shell buried some men, killed 6 and wounded 26. A further 4 were killed and 3 wounded while fetching rations.

On the 5th half the Battalion went into the front line. The next day they stood to, concerned about a possible German attack, but it came to nothing. Acting on orders they sent two parties to the German trenches to try and capture prisoners - presumably to gain intelligence before the attack, but they were seen and were lucky to get back with no casualties. On the 7th they were ordered to send out two strong patrols because they had received information that the enemy were withdrawing. Each patrol consisted of one officer and thirty men. One party reached the first line and indeed found it lightly defended and they captured two Germans. The other party continued to the second line, but were not so successful with one man wounded and five men, including the officer, captured. On the 8th, perhaps because the Germans were now anticipating the forthcoming attack, the diary recorded that the enemy was nervous all day.

On the April 9th at 5:30am, after five days of bombarding the enemy lines, the Battle of Arras started with a creeping barrage. This was a standard tactic, the artillery aimed to land their shells just in front of the advancing men, moving the barrage forward in front of them. In theory the enemy would then be forced to keep their heads down and so the advancing men were protected. In practice the men were often advancing over difficult ground and the speed at which they could move was not always predictable. When they got it wrong the men were either shelled by their own guns or, often more likely, the curtain of shells left them behind and the Germans simply stood up at the posts and fired into the advancing troops.

On this day, at least for George’s Battalion, it seemed to work; they were in the front line of the advance and their final objective, the Glasgow Trench, was reached. Amazingly, during their action, they only had 2 officers and 4 other ranks killed, although 7 officers and88 other ranks were wounded and 19 more listed as missing, but they now held the Glasgow Trench.

Although George Trussell is officially recorded as ‘killed in action’ on the 10th, the Battalion’s war diary clearly states ‘Casualties NIL’. We know that his body was never found so it seems almost certain that he was one of the missing nineteen men of the day before, and so that was probably the real date of his death, April 9th – the first day of the Battle of Arras.

Officially the battle lasted from April 9th to May 16th. The Commonwealth War Graves Commission estimates the number of British troops dead, missing or wounded as nearly 170,000, but that figure does include the losses from the reduced level of fighting, which continued to the end of May.

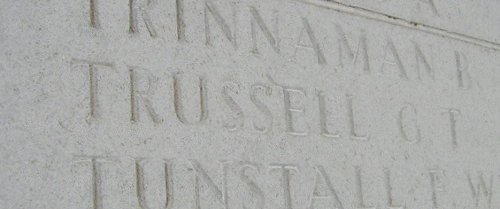

The men whose bodies were never found or never identified are recorded on individually unique memorials. George Thomas Trussell’s name appears with four other Pirton men on the impressive Arras Memorial, which stands on the western edge of Arras. The names on this memorial and the associated cemetery lie behind huge brick and stone walls, and they are protected from the bustle of the modern world by this impressive fortress-like structure. The cemetery holds 2,651 Commonwealth burials from the First World War, but George is amongst the 34,717 names of the men from the United Kingdom, South Africa and New Zealand who died in the Arras sector between the spring of 1916 and August 7th 1918. None of these men have any known grave.

(*1) Ellen (bapt 1885), Emily (b 1886) and George Thomas Trussell (b 1888).

Additional Information

Text from the book: The Pride of Pirton

Acknowledgments

The Pride of Pirton book – www.pirton.org.uk/prideofpirton Chris Ryan / Tony French / Jonty Wild